A friend living in the southern US opened her front door, and literally froze. There was a dangerous snake on her porch. Doing its best to protect her, her nervous system froze her body.

A friend living in the southern US opened her front door, and literally froze. There was a dangerous snake on her porch. Doing its best to protect her, her nervous system froze her body.

Dr. Stephen Porges’ Polyvagal Theory explains the way evolution dictates how the nervous system and body respond to danger signals in the environment. His theory has transformed the way we view trauma and chronic illness and has raised the status and relevance of the vagus nerve to be a popular topic in mainstream magazines. Dr. Porges discovered that the vagus nerve, which innervates most of our organs, has different branches, and that the autonomic nervous system reacts to danger in a hierarchy of three possible responses. The first line of defence in the face of a perceived threat is activation of the most recently evolved social engagement system. We try to negotiate safety through our words, tone of voice, eye and facial expression, and gesture. The face, eyes, inner ear and mouth are innervated by cranial nerves associated with the ventral vagus nerve. The psoas is involved in this response by “faking it”. If I sense that the person in front of me is unsafe, I can appear outwardly calm but my psoas muscles are gearing up for the next response, fight or flight.

Unfortunately, negotiating safety doesn’t work with a snake! So my friend’s nervous system inhibited her vagal calming and social engagement system and activated the second line of defence, the fight or flight response. Safety through mobilization, running away or fighting, is enabled by activating the main muscles associated with this strategy, the psoas muscles.

You can’t really fight with a snake, and movement often triggers a snakebite, so my friend’s nervous system inhibited the fight or flight response and activated the most primitive response to danger, system shutdown or freezing. The dorsal part of her vagus nerve activated neural circuits that would raise her pain threshold, decrease metabolism, slow breathing and heart rate and even cause her to dissociate, all of which would increase her chances of survival in a life-threatening situation.

Luckily, the snake slithered away. The instinctual response of my friends nervous system may have protected her from a fatal snakebite.

The response of the psoas to trauma has effects on physical, mental and emotional levels:

- BREATH: The psoas muscles and the respiratory diaphragm co-contract because of their intimate fascial connections. Fear results in breath constriction, and over time, chronic breath dysfunction can change blood chemistry and contribute to chronic illness, mental fogginess, emotional volatility and a host of other conditions.

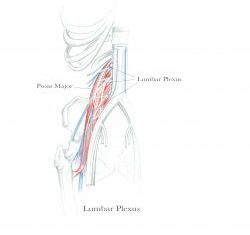

- DECREASED SENSORY AWARENESS: The lumbar plexus, the collection of nerves that supply the pelvis and legs, is embedded in the psoas. The extensive fascial component of the psoas contains large numbers of sensory nerve endings. Research has found that interoception, the ability to sense inner sensations, is deeply compromised by trauma. No wonder! The nerves are compressed by tension in the psoas, which dampens their ability to receive and transmit sensory information.

- DISCONNECTION FROM CORE: In his book, “Trauma-Sensitive Yoga in Therapy”, David Emerson suggests that traumatized people “… do not have a reliable self, a feelable self, a foundation from which to safely experience themselves, relationships, and the world around them”. Carefully and patiently working with the psoas can help to establish a felt sense of a centre that can become “a touchstone” for self-knowledge and self-support.

- CHRONIC PSOAS CONTRACTION SIGNALS CONSTANT DANGER: When trauma is not processed skilfully, the psoas muscles remain contracted, signalling the nervous system to ALWAYS be on alert and ready to fight or flee. Over time, the poor adrenal glands become exhausted from constantly pumping out adrenalin, cortisol and other stress hormones. This sets the stage for stress-related illnesses.

- BURIED MEMORIES: In my experience, the psoas muscles are a physical repository of traumatic memories and emotions. Sensory stimuli associated with the original trauma, and unskillful psoas release work can cause these memories to erupt, which can essentially re-traumatize someone.

Accessing the psoas in a trauma sensitive way can build resources at the same time traumatic memories are released from the tissues. Stay tuned for next month’s blog on how the psoas protocol can help people to heal from trauma.